Merriam-Webster has decided that “irregardless” will be included in the next edition of their dictionary. A number of old and dear friends have greeted this news with alarm and dismay. In response to the brouhaha prompted by their decision, the dictionary’s staff wrote in their “Words of the Week” roundup:

Irregardless is included in our dictionary because it has been in widespread and near-constant use since 1795. We do not make the English language, we merely record it.

Please don’t misunderstand me: “irregardless” is an ugly and unnecessary word, birthed from a misunderstanding of what “regardless” means (much as the execrable “flammable” came about through a misunderstanding of “inflammable”). I will not use it, and will also encourage my students not to do so. Still, the people at Merriam-Webster are right about how language works. Language is a living thing. Old words pass out of use and new ones emerge continually. Likewise, the meanings of words are not carved in stone, but depend upon how they are used.

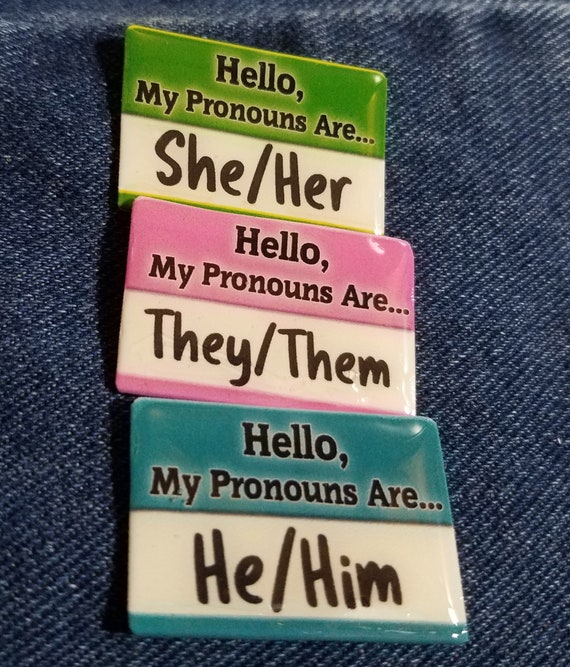

Sometimes, our language debates are a source of pain and controversy far beyond the “irregardless” fracas. The word “they,” our English third person plural pronoun, has for some time been emerging as the gender-neutral singular pronoun our language lacks. Many transgender and gender-fluid folk prefer “they” to the rigidly binary “he/she.” This use of the pronoun irritates and angers some, and even prompts hostility and ridicule. But we cannot pretend that English grammar is so rigid as to disallow this use. Much like the despised “irregardless,” the singular use of “they” has deep roots in the English language, going back to 1300, and including such notaries as Emily Dickinson, who wrote in an 1881 letter, “Almost anyone under the circumstances would have doubted if [the letter] were theirs, or indeed if they were themself.”

The flexibilities and peculiarities of language become heightened when one language is translated into another–particularly, when the translated text carries the cultural and religious weight that the Bible does. Consider the translation of 2 Timothy 3:16-17. In the CEB, this passage reads:

Every scripture is inspired by God and is useful for teaching, for showing mistakes, for correcting, and for training character, so that the person who belongs to God can be equipped to do everything that is good (compare KJV and NRSV of these verses).

The phrase in bold print is a single word in Greek: theopneustos. Here the CEB follows other English translations, including the NRSV and the venerable KJV, in rendering theopneustos as “inspired by God.”

But the New International Version famously renders this verse “All Scripture is God-breathed.” That is, literally, what theopneustos (combining the Greek words for “God” and “breath”) would seem to mean. This reading of theopneustos is followed in the ESV, and in Eugene Petersen’s popular paraphrase The Message. Christians who insist upon the Bible’s inerrancy–that is, its absolute and infallible authority–often cite this passage. Surely, if the Bible is God-breathed, that must mean that its words are God’s very words, as perfect and infallible as God is, and carrying God’s own authority.

But the derivation of a word is not necessarily a reliable guide to its meaning. For example, the “literal” meaning of the word “sarcophagus,” derived from Greek words meaning “flesh” and “eat,” would be “carnivore”–which of course is not what the word means at all. Surely, a better guide to what theopneustos meant to the author of 2 Timothy would be how the word is actually used.

Unfortunately, this word is uncommon: it appears nowhere else in the New Testament; nor is it used in the Greek translation of Jewish Scripture, the Septuagint. Outside of the Bible, the term is no less obscure. In the Sentences of Pseudo-Phocylides, a first-century Jewish philosopher, theopneustos is used to distinguish wisdom from God from human wisdom (Sentences 129). However, as P. W. van der Horst observes, “This line, in clumsy [Greek], is probably inauthentic. It is lacking in some important textual witnesses” (The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, Vol. 2, ed. James H. Charlesworth [Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1985], 579). Placita Philosophorum is a compendium of the teachings of the philosophers, ascribed to the first-century historian Plutarch (but almost certainly from after Plutarch’s time). In the chapter on the source of dreams, the teaching of Herophilus is cited:

dreams which are caused by divine instinct [theopneustos in Greek] have a necessary cause; but dreams which have their origin from a natural cause arise from the soul’s forming within itself the images of those things which are convenient for it, and which will happen (Placita Philosophorum 5. 2. 3).

Perhaps, then, characterizing the Bible as theopneustos likewise means that unlike ordinary books, the Bible is a holy book–a book inspired by God.

What then does it mean to say that the Bible is inspired by God? Another way into this question would to ask what we usually mean when we speak of inspiration (a word also related to breath). Methodist theologian William Abraham considers what we mean when we say that a teacher is inspiring, or that a teacher’s students have been inspired:

. . . there is no question of students being passive while they are being inspired. On the contrary: their natural abilities will be used to the full extent, and as a result they will show great differences in style, content and vocabulary. Their native intelligence and talent will be greatly enhanced and enriched but in no way obliterated or passed over. . . . there need be no surprise if, from the point of view of the teacher, they make mistakes (William J. Abraham, The Divine Inspiration of Holy Scripture [Oxford: Oxford University, 1981], 63-64).

Applying this analogy of classroom inspiration to Scripture, Abraham concludes that the writers of the Bible, likewise, should not be understood as inerrant automata, mechanically transmitting the actual words of the Divine. He writes:

We must allow a genuine freedom to God as he inspires his chosen witnesses, knowing that what he does will be adequate for his saving and sanctifying purposes for our lives. In so doing we escape the tension and artificiality of those theories that have staked everything on the perfectionist and utopian hopes that stem from a theology of Scripture that substitutes divine speaking [i.e., “the Bible is the actual, literal word of God”] for divine inspiration without biblical or rational warrant (Abraham, Inspiration, 69-70).

While Abraham’s statement that the Bible is “adequate” to God’s saving purposes may seem to us far too weak, it is not much different than the claim that the writer of 2 Timothy makes. This passage affirms that God-inspired Scripture is ophelimos–a word also not found in the Septuagint, and found in the NT only in 2 Timothy and Titus, but relatively common in Greek literature. It means “useful”–not infallible, not inerrant, not even authoritative, but “useful.” In particular, this passage says, Scripture is

useful for teaching, for showing mistakes, for correcting, and for training character, so that the person who belongs to God can be equipped to do everything that is good.

Reformed theologian Daniel Migliore draws an important distinction: “Scripture is indispensable in bringing us into a new relationship with the living God through Christ by the power of the Holy Spirit.” However, “Christians do not believe in the Bible; they believe in the living God attested by the Bible” (Daniel L. Migliore, Faith Seeking Understanding: An Introduction to Christian Theology, Second Edition [Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2004], 50). The Bible is not “God-breathed”: inerrant and infallible. But the Bible is a sufficient, Divinely inspired means to a glorious end!

As a Bible teacher, Willie Abraham’s classroom illustration resonates strongly with me. I do indeed hope that I inspire my students. But by that, I certainly do not mean that I expect them to repeat my own words by rote, or even that I expect them to think just as I do. I do hope that they will love the Bible as I do, and that through their study they will be led into a deeper and deeper relationship with the God of Scripture–which is the Bible’s purpose.